This year’s international climate negotiations (also referred to as COP 26) have been criticized by many for being the most exclusive and inaccessible negotiations ever. Many voices, including those of youth, grassroots women, indigenous peoples, and vulnerable communities, have gone unheard. As a result, the outcomes of COP 26 “reflect the lack of fair access and participation of many civil society organizations, especially from the Global South whose role as observers (in these international processes) is essential for climate justice in their regions”.

In this blog post, Ndivile Mokoena shares her views and thoughts on the importance of putting grassroots women and their communities at the center of combatting climate change and reflects on what this means for national and international climate governance and decision-making. Ndivile is a South African climate activist and feminist campaigning for gender justice in climate policy. She is working with GenderCC Southern Africa as a Project Coordinator.

Connecting women’s rights, gender equality and climate justice

Gender must be a central consideration in the context of climate change because of long standing social and gender inequalities. Due to these inequalities, women are often disproportionately affected by climate change and its impacts. Women, for example, commonly face higher risks and greater burdens from the impacts of climate change in situations of poverty, and the majority of the world’s poor are women. In addition, the fight against climate change is not only a struggle to keep our planet livable. For many women, climate change can be a direct cause of violence. During periods of prolonged drought, for example, women and girls make more frequent and longer journeys to obtain food and water, which makes them vulnerable to gender-based violence. Research has shown that girls who spend more time fetching water have fewer days in school and may even drop out.

Yet, women play a critical role in response to climate change due to their local knowledge and leadership, for example, in sustainable resource management and/or in leading sustainable practices at the household and community level. Their unique knowledge and skills can help make the response to climate change more effective and sustainable. However, women’s unequal participation in decision-making processes and labor markets compound inequalities and often prevent women from fully contributing to climate-related planning, policy making and implementation.

In South Africa where I am from, climate change poses a lot of challenges for agriculture as it is the cornerstone for most poor communities. Drought is a major problem for small scale farmers as it leaves the soil hard to cultivate resulting in significantly diminished harvest. Local women farmers can play a vital role in the promotion of climate resilient practices in agriculture if they are empowered enough. However, there seems to be no political will from authorities to help small scale farmers, especially women. This is compounded by greed and corruption within the system.

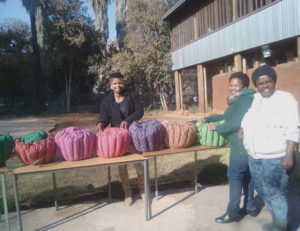

At GenderCC Southern Africa, we train local women farmers on agroecology and permaculture farming to overcome challenges posed by erratic weather conditions and climate change impacts. This provides them with unique knowledge and skills that can help make the response to climate change more effective and sustainable. It also helps them to be more respected and given an opportunity in the current male dominated positions. Communities, including women, often lack control over their own energy systems as well as over other natural resources.

At GenderCC Southern Africa, for example, we therefore embarked on a train-the- trainer programme on renewable energy and energy efficiency. We identified Champions from community projects to be trained on how to use small-scale renewable energy products. In turn, they then trained other interested parties at community level to become entrepreneurs that will run their own local renewable energy and energy efficiency hubs/cooperatives/businesses where communities could be able to buy a wide range of products and receive technical assistance.

These trainings provided the Champions with ‘green skills’ partnered with key business skills and entail alternative energy sources (including renewable energy products and wonder bags for retaining temperatures made from reusable materials). The primary goal within energy and resource democracy should be for communities, particularly women, to be empowered to make decisions over the use of local resources and the best way to fulfil their needs. This transition must challenge the gendered division of labor, which places women in often low waged, insecure, and informal subsistence and service industries. It should re-interrogate the very notion of labor so that unpaid care and domestic work, mostly assumed by women, is valued, recognized, reduced, and redistributed. These reproductive activities provide the invisible backbone of welfare and wealth for any given society. This invisibility deprives women of the skills and capacity to participate in the economy beyond household responsibilities.

National and local governments are already facing the challenging task of mainstreaming climate change into all relevant sectors – from housing and energy to transport and waste. The requirement of integrating a gender-responsive approach (i.e., making sure that gender norms, roles and inequalities are taken into consideration and that action is taken to eradicate them and to overcome historical gender biases and androcentrism) might seem daunting. Integrating gender into the climate change agenda is a very complex, long, and unwinding process, which is heavily influenced by the context, politics, and various stakeholders in each country. Even, within each country, the context of each region is different and as a result, it is often hard to come up with a one-size-fits-all approach that can be adopted universally.

Yet, just as climate change is not gender neutral, climate responses have been shown to be more effective and equitable when social dimensions such as gender are addressed. Therefore, climate policies must connect to climate, development and gender. It is very important to work closely with grassroots women and their communities to ensure that this work is done effectively and efficiently (bottom-up approach) to work at all levels, locally and nationally and to ensure that the experiences of grassroots women are taken up into and addressed in national and international processes. In the long-term, transformative change is needed in gender justice and climate justice.

What does this mean for gender justice in national and international climate processes and negotiations? Some recommendations:

🔹 Women’s full participation at all levels of environmental and climate governance is crucial.Women and girls are currently underrepresented in climate decision-making and leadership positions. This needs to be increased throughout climate and environmental governance and sectors relevant for transitioning to an inclusive, circular, and regenerative green economy.

🔹 Gender equality needs to be mainstreamed into country’s national plans to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. They must create a just and equitable transition for all and ensure that climate solutions are gender-just and inclusive of indigenous peoples and local communities, their knowledge, and practices.

🔹Just climate solutions also require intersectional approaches to be integrated at every stage of development, implementation, and monitoring of climate policies, plans and solutions. In our deeply unequal societies, gender interacts with sexuality, race, national origin, age, class, disability, and other identities to shape people’s access to power and resources, leaving some disproportionately impacted by and vulnerable to climate disruption. An intersectional gender lens must be integrated at every stage and rhetoric must match reality.

🔹 Ensuring gender justice in national and international climate processes requires adequate financing. While increased discussion of gender equality is warmly received, we want to see tangible results, and this requires funding to match the rhetoric.

🔹 Climate actions must promote gender responsive energy democracy and move us away from top-down, market-based approaches for energy production, distribution and control over natural resources and move towards an economy of care. The world needs to break free from fossil fuels and unsafe energy systems.

🔹 A gender responsive, ecosystem-based and community-driven approach to climate change adaptation and resilience is needed. This will allow us torestructure false solutions to climate change brought about by corporations who greenwash projects that bring about land grabs, genetically-modified foods, monocropping and heavy chemicals in industrialized agriculture as opposed to local community-led ecosystem restoration measures.

🔹 World leaders are encouraged to adopt gender-just climate policies that focus on the economic benefits of climate action, with a strong emphasis on job creation. Covid-19 has highlighted the need for real, transformative change in the way we think about economic policy domestically and internationally. This transformation must center around and resource care work, investing in unpaid care work and social protection and acknowledging the contributions of women and girls in it.

Interested in reading more about the work of Ndivile with GenderCC Southern Africa? Check out this link: https://www.gendercc.org.za/

Cover photo credit: OXFAM (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)