The mining model, as implemented in Brazil, of promoting the extraction of natural resources by the state in conjunction with transnational companies has caused countless socio-environmental conflicts. Mining profoundly modifies production and reproduction in life in the surrounding area, deepening inequality, as does patriarchy, destroying community ways of life and causing an immense environmental impact through the intensive use of electricity and water.

A typical example of this predatory structuring was in the Rio Doce river basin which was entirely ruined in the biggest socio-environmental disaster in Brazilian history when the Samarco tailings dam (belonging to the Vale S.A and BHP Biliton joint venture) burst on 5 November 2015, causing 19 deaths and one miscarriage and affected 1.5 million people. The mud destroyed the entire river and several tributaries up to the coast at Espírito Santo. Two years on and there are still hundreds of fishermen who cannot ply their trade, farmers who depend on the river for planting, towns depending on the river for their water supply and families who have lost their homes. Still, the companies responsible don’t face charges and are still running the territory without the slightest pressure from the state or involvement of the communities affected.

The mud destroyed the community way of life and it is women who are most affected due to the imposition of the patriarchal attitude that looking after children and running homes was the role of women. When community links were broken these women lost the community support network with close family with whom they could share child care, problems or support for health problems and emergencies. In addition, loss of leisure spaces like the town square, the river, the waterfalls and community entertainments has contributed to locking women up even further in the private space of the home.

Through my work at MAB I came across several testimonies of affected women whose work is not being taken into consideration, as it is viewed as informal, such as working the land or informal sales or exchange arrangements. The situation of family garden produce is typical. This was ruined by the arrival of the mud. Many women provided food sovereignty through the varied crops from their gardens. They never had to buy produce in the market. So far, most of these women have received no compensation or emergency aid to compensate for this activity. The dam bursting also buried livelihood projects, many of which related to women’s financial independence, like that from the growers in Gesteira who had started a cooperative have been destroyed by the disaster.

In addition, the company’s distribution policy for emergency aid cards focussed on those they considered as heads of household, mostly men, thus endangering women’s financial independence once family income was again concentrated in men’s hands. Clearly this practice demonstrates that the companies are ignoring women as political beings in discussing rights policy. Dreams and hopes were washed away by the mud and are being buried deeper when the voices of the women affected are not listened to in deciding the future of their lives and communities, and when they are not allowed the right to re-establish collectively, the only way of ensuring community links will be rebuilt.

A further aggravating factor is men losing productive work resulting in depression, increased alcoholism and drug abuse leading to increased violence against women. Take the example of fishermen whose traditional family pattern was for them to be working away at sea for 10 days. The presence of the man at home with no work to do has resulted in increased domestic conflict. As regards violence, we can also point to the reconstruction work in the areas destroyed that has also attracted other workers to the area and directly contributed to increased cases of sexual abuse and violence.

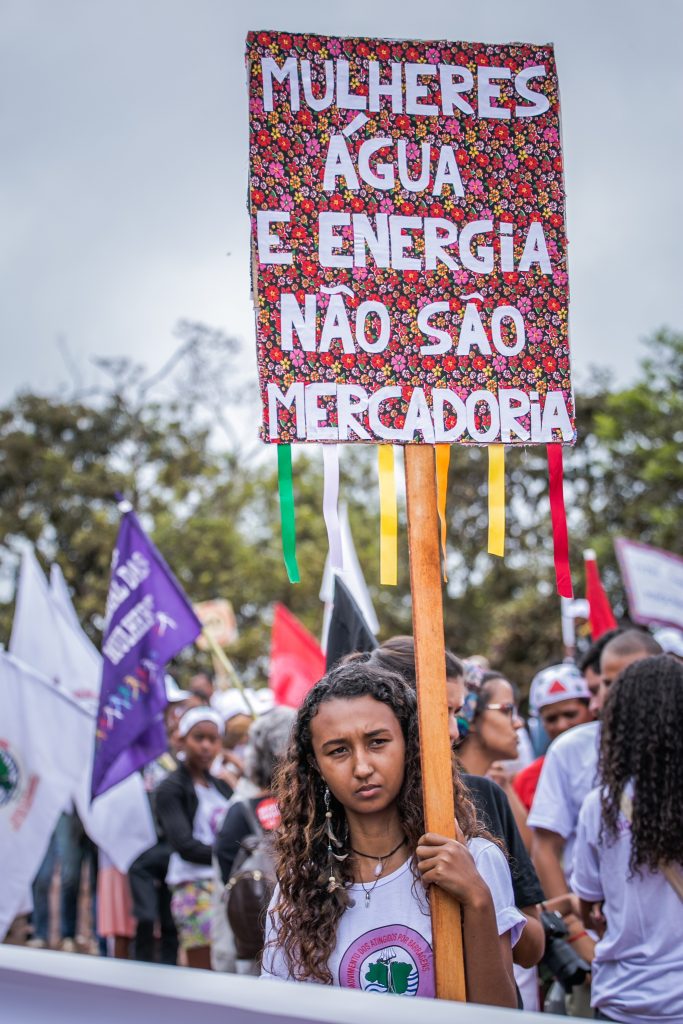

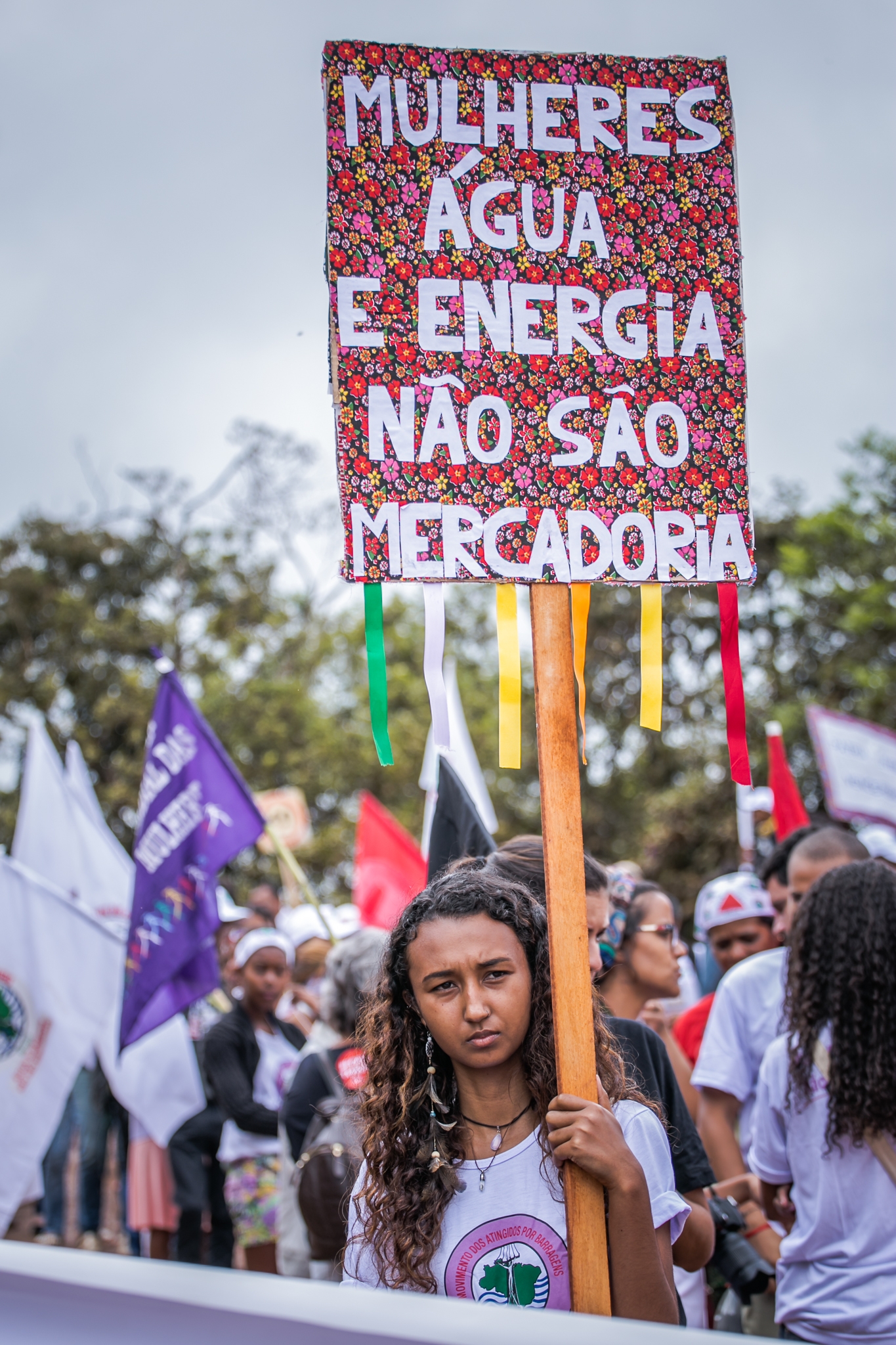

I believe however, that the basin is not just made of tears. I have seen that it is the very women affected who are the seed of reconstruction. They are building fairer development for communities, as they become the ones who lead the process of resistance in our lands, fighting courageously for respect for community ways of life and being in the front line denouncing abuses of power by the companies. If there is any chance of rebuilding live along the river, based on the people’s conception, it will begin with the colour lilac.

Tchenna Maso is a people’s lawyer with MAB, (Movimiento de Afectados y Afectadas por Represa/Brazil [The movement of the people affected by the dam/Brazil]) who works on gender equality in human and company rights. She is a law graduate of the Federal University of Paraná and has a masters in political science from UNILA (The Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-americana [Federal University for Latin American Integration]) in contemporary integration in Latin America.