The harmful impact of the mining industry incites resistance in local communities around the world. Below is what representatives of local movements have told us about this fight- a fight which is also supported by the Church.

Edwin doesn’t give up. Neither do Ana and father Joy. There are hundreds of women, men and communities like them, who are fighting the battle against the giant that threatens to devour them and the environment they live in from many different corners of the globe. This giant is the mining industry, with all the aftermath of violence that it causes. Behind deep excavations that hurt the land or the disintegration of the rocks to extract precious materials, there are the big multinational companies and their interests, with their potential to intimidate those who want to stop projects that are harmful to the environment and to the people who live there. Alongside struggling communities, however, are the local churches that have embraced the preferential option for the poor that the encyclical of Pope Francis Laudato Si’ states right from the start in ecological terms, which for many people seemed a new attitude for the Church.

Father Joy, Edwin and Ana are just some of the protagonists of these struggles. Thirty of them, representatives of the local communities affected by extractive activities in mining areas, from America, Africa and Asia came together in Rome, in a three-day meeting (17-19 July) hosted by the Salesianum. The meeting, entitled “In union with God we hear a plea“, was promoted and organized by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, chaired by Cardinal Peter Turkson, in collaboration with the Latin American network “Iglesias y Mineria” (Church and Mining). As the Pope wrote in his message to the communities invited to Rome: ” A cry for lost land; a cry for the extraction of wealth from land that paradoxically does not produce wealth for the local populations who remain poor; a cry of pain in reaction to violence, threats and corruption; a cry of indignation and for help for the violations of human rights, blatantly or discreetly trampled with regard to the health of populations, working conditions, and at times the slavery and human trafficking that feeds the tragic phenomenon of prostitution; a cry of sadness and impotence for the contamination of the water, the air and the land; a cry of incomprehension for the absence of inclusive processes or support from the civil, local and national authorities, which have the fundamental duty to promote the common good.” Their resistance and their conviction in the strength of their reasons are the key elements of the testimonies that we have gathered in Rome from the representatives of the communities affected by mining activities.

The invasion of multinationals and the impact of the mining industry

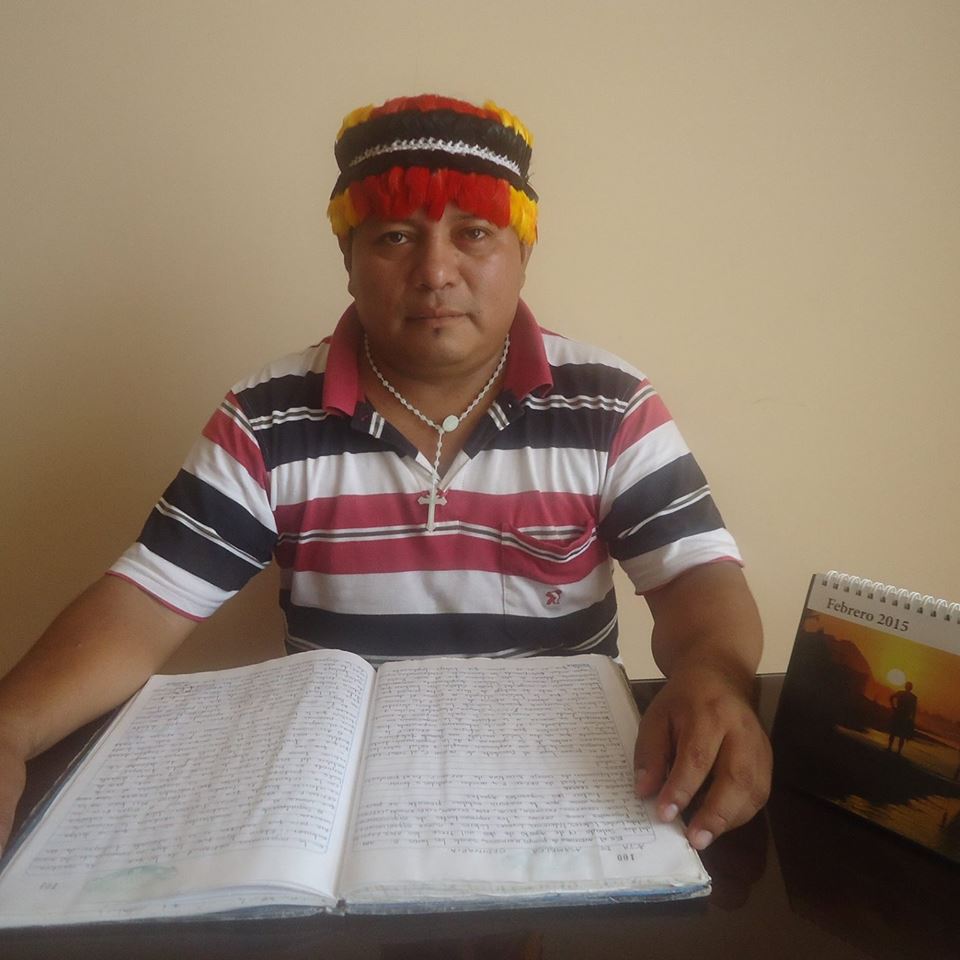

The story of Edwin Davila Montenegro seems to be rooted in an episode, which took place several kilometers away from his homeland. “In 2013,” says the 39-year old Peruvian who belongs to the Amazonian ethnic group Awajun and is a representative of the Wampis ethnic group also, “I went to visit the French Minister of Environment in Paris (at the time it was the Socialist Philippe Martin), thanks to the support of ‘Secours Catholique’. When I showed up in front of him I was dressed in the traditional way, with a crown of feathers and a red dress.” He had had a three-day journey to arrive in the French capital, including a boat ride, several hours by bus to the capital Lima, and then a plane trip to Europe. “The Minister was very surprised to see me with my traditional clothes. When I showed him the papers against the mining establishment signed by the people I represent, a community of 65,000 people in total, the Minister apologized a thousand times for the presence of the French company and for the harm it had done to my people. ‘I promise to dialogue with the management and the leadership of the company. I’ll write to you’, he guaranteed to me. But since then I have never received an answer.”

Edwin

The company in question is the French oil company Maurel et Prom1. Along with the Canadian Pacific Rubiales, which extracts oil and gas, under the direction of the Colombian mining company Afrodita. These companies have been the key players in gold extraction in the province of Condorcanqui, in the Peruvian Amazon since 2007. “They extract the gold on the mountain” says Edwin. “But this way they pollute the source of the river Senepa (at the border with Ecuador). The pollution then goes downstream.” The open pit mining of gold uses large amounts of cyanide, which is highly toxic to plants and animals. Even the Pope reflects on the environmental damage caused by gold extraction, whom in the encyclical writes, “Often the businesses which operate this way are multinationals. They do here what they would never do in developed countries or the so-called ‘first world’.” (Laudato Si’, 51).

The environmental impact of mining activities is large: “The water that reaches the villages is contaminated, it is no longer drinkable, so that to drink we have to look for water in the high grounds” says Edwin. As a result of this the animals die. More than 3000 square meters of land were subject to deforestation. “At first our children were bathing in the river, but they came out with spots and irritation on the skin. We haven’t been back for a long time”, added the spokesman of the Awajun group. “Still today we can no longer eat the animals, because they drink also from polluted sources, and the fish that are traditionally part of our diet.” Then there is the effect on culture: “Even the craft was destroyed, since extracting clay, which we have used to forge objects for centuries, has become a health hazard.” The mine has taken away the soul of the Indigenous.

Local communities, global resistance

Nobody asked the opinion of the Amazonian community on the establishment of the mine. Multinational companies seem to not have the habit of doing this. Yet this consultation is required by the International Labour Organization, when it requires the “free and informed prior consultation of indigenous or aboriginal peoples for all kinds of projects that are installed in their territories” (Convention 169). “It is essential to show special care for indigenous communities and their cultural traditions”, the Pope warns in the encyclical (Laudato Si’, 146), that they should be “the principal dialogue partners, especially when large projects affecting their land are proposed”

From Peru to Guatemala, the music does not change. The 22 year old Ana Sandoval participated in the struggle of the community of San José del Gulfo and San Pedro Ayampuc, in Guatemala. The area from which she comes was invaded by a mining project a few years ago, part of a larger plan with 15 exploration areas, all concentrated in the small and already overexploited Guatemala, called “Progreso 7 Derivada”. The extraction of gold and silver is operated by the Guatemalan company Exmingua, a subsidiary of the US company Kappes Cassiday & Associated (KCA) with the Canadian Radius Gold. Three multinationals operating in a small territory (Guatemala), once again inhabited by indigenous communities. Ethnic minorities are often not protected by the state, or they are only protected on paper.

The entire area where Ana grew up is subject to contamination by arsenic, so much that the concentration of this element found in the community of San José is much higher than the limits recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Rocks in this area already naturally contain large amounts of this element which pollutes water and air. When a mining establishment starts its extractive activity, it also adds the use of another toxic component to the environment: mercury, used to purify gold.

The first warning sign for the inhabitants of San José was the lack of water. “We realized that it was not coming, but we did not know why,” says Ana. “To our request for explanation, the Health Ministry said that information is confidential. It is known how arsenic and mercury produce devastating effects on the skin and blood.”The community responded to the omissions of the authorities with mobilization. “In 2011 we were told that there were no plans for San Jose, or maybe just that a shopping mall would be built. But we realized that it was a trick. So in March of 2012 we went to block a machine which was digging. The whole community mobilized itself. We told ourselves: we won’t move from here.”

And so it went on for over three years, the people of La Puya (this is what the fighting community was called) stayed peacefully to guard the entrance of the mine. Shifts were organized with at least 25 people around the clock. Whoever was on site organized school activities or entertainment for children who were also on the resistance site. Those who couldn’t be there showed their support in other ways, for example by bringing food to those who were in front of the mine. This protest camp, estimated Ana, involved a total of 22,000 people.

A phenomenon of community and shared resistance was equally at the center of the struggle of Awajun and the Wampis in Guatemala. Edwin, a representative of their protest, is actually the spokesperson (‘vocero’ in Spanish) of 65,000 indigenous people and gets his authority from a complex system of grassroots organizations. A system that Edwin describes in this way: “On the rio Santiago there are 62 communities with as many leaders, called ‘apos’. The apos get together and create a federation. Then there is a General Assembly which elects the president of the federation. In the province of Condorcanqui there are 12 federations each with 60 or more communities. I represent all this.”

What unites the experience of the two Latin American communities is the repression they are facing. In Guatemala violence was unleashed on protesters in 2014. “In May the police attacked us with tear gas, poles and stone” recalls Ana, who was present when the attack occurred. “A companion, Eva, was hit by a tear gas bomb. Many others had broken bones.” Today in San José the mine is in operation: the police are on one side and on the other side is the ongoing protest of the local community.

Struggles of the community of San Jose’

In the Peruvian Amazon police, repression came when, in 2009, 6,000 people occupied an oil well. From there they continued a week later , arriving in the regional capital Bagua, joined by 5,000 other native Americans “We blocked the road for 15 days,” says Edwin. “Then we got to the capital of the region, Bagua, and we blocked the entire city to make our voices heard. The protest went on for 54 days. The government did not respond to our appeals. We marched peacefully and the response of the institutions was to evacuate us by force”. There were about one hundred deaths among the indigenous and 24 among the police a missing military officer (whose body has been recovered), 204 injured and 700 people who ended up in prison. Edwin argues that the victims among the police were related to internal conflicts, since many of them sided with the local communities,

The Baguazo, as these days of protest are called by the people, have also generated judiciary issues. 52 people are still under awaiting trial, and among these, eight have immediate arrest warrants. Edwin himself lost a brother and a nephew in the fight.

The Church as witness

Among those occupying the San José mine, a mass is held once a month to say thank you for staying to resist. After the clashes in Bagua, the local Church played an active role in stopping the repressive actions of the police and the military. Local churches are well aware of the weight of the repressions and intimidations, occurring through violence by the paramilitary forces or through attempted bribery of the protests’ leaders.

The province of South Kotabato, an island of Mindanao in the southern Philippines. The Saggittarius Mines Inc. (SMI) has been working for the Swiss mining company Glencore Xstrata on project Tanpakan for the extraction of copper and gold. “They are still in the exploration stage, but there are already many problems for the environment,” states Father Joy Pelino, a priest who works in the province of Kotabato. The huge mine, in addition to the potential environmental impact, spreads largely in an area inhabited by indigenous Blaan, who because of their opposition have suffered strong intimidations. The process of persecution and the criminalization of leaders committed to defending their lands and their rights is a strategy constantly employed by mining companies on local populations. And which Father Joy, on behalf of the local church of Mindanao, does everything to oppose.

“The Environmental Law of the Philippines prohibits the exploitation of a mine like this one, which is open-air and very large (1.2 km diameter),” notes Father Joy. “The company, however, says that this is a more practical and economical solution.” The project will cover 10,000 hectares, 4,000 of which are very rich in biodiversity, with particular flora and fauna. Six rivers and the lake in which they stream will therefore be contaminated, altering the agriculture of the area (where they grow pineapples, bananan, rice and corn), and the fishing, if the project goes ahead.

Again, the environmental impact affects the most vulnerable layers of the population: the ethnic minorities. This is what is called ‘environmental racism’. “The well is designed in the living area in the territories of indigenous Blaan. If all goes as the company asks, they will be evicted.”

For the indigenous people, land is everything: their identity, their soul, their roots. The Blaan were the first inhabitants of Mindanao. This is why they resist this mining project, and for this they have paid a high price for the defence of their rights. “Although we are only in the preparatory phase, 15 people were killed in the last three years (including a whole family and two resistance leaders, father and son)” Father Joy states. “It is suspected that the perpetrators are military officers and private security agents.”

The local church has sided,without reservation, with the Blaan. It has denounced violations, promoted the dignity of indigenous peoples, called for respecting the right to self-determination, security of the people and ability to live in peace. As a result of these complaints, the military officials accused of crimes against indigenous people are now being tried before the martial court. “Convinced that mining cannot balance out its environmental and social costs, we presented a petition with 100,000 signatures to the President of the Philippines, and the Blaan community delivered 1,000 signatures to the National Commission for Indigenous Peoples asking them to stop the project of Tanpakan”.

Why does the church of Mindanao doall this? “It’s our duty to pursue justice and the common good for all communities affected by mining”, insists Father Joy. “That is the central mission of the Church that preaches the Gospel.”

The demand for justice that comes from the community and local churches also echoes and finds a source of encouragement in the words of the Pope, when he invites the mining industry to change in the name of “integral and sustainable development”, as indicated in the encyclical (Laudato Si’, 13 ). In his message for the event ´United in God we hear a plea´ Pope Francis writes that The entire mining sector is decisively called to effect a radical paradigm shift to improve the situation in many countries. To this change a contribution can be made by the governments of the home countries of multinational companies and of those in which they operate, by businesses and investors, by the local authorities who oversee mining operations, by workers and their representatives, by international supply chains with their various intermediaries and those who operate in the markets of these materials, and by the consumers of goods for whose production the minerals are required”

Local communities affected by the mining industry are hoping now that the church will listen to the cry of their suffering people. It’s the right time to do it, they say.

United Nations

How does international law relate with globalization issues? Can a multinational corporation, not necessarily belonging to the mining sector, be held responsible for violations of rights and abuses on the population? And if so, in which country should it be pursued; in the country of origin (where the law is usually more compelling) or in the one where it operates? Under the pressure of the Treaty Alliance campaign, which brings together hundreds of secular and Catholic organizations and movements, the UN Human Rights Council approved with a majority (although the European Union, the US and Japan opposed and Brazil abstained ) a resolution in 2014 requiring the writing of a Binding Treaty on the issue of violation of human rights by multinational corporations. “A victory for the little ones,” points out Frei Rodrigo Peret, Franciscan of JPIC & Mining Project and member of the Treaty Alliance. “This decision by the United Nations gives states back a task that industrial interests had taken away from them: putting a stop to the abuses caused by globalization.” A UN subcommittee had put forward a set of norms for corporations in 2003, but these were not approved. In 2005, the then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan gave the U.S. academic John Ruggie the role of Special Representative for Business and Human Rights. Ruggie produced guidelines to assist companies in avoiding human rights abuses which were adopted in 2011; these are called UN Guiding principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). Many NGOs, however, have criticized two aspects of the guidelines by Ruggie: they are not binding principles for companies and the remedies were decided by the same corporations that committed the violations. Those criticisms started the change which was later sealed by UN Human Rights Council. The working group for the drafting of the treaty met beginning in July 2015.

Ernest

The effects of mining activities do not spare the First World either. Amongst the most serious results, is the disaster of Mount Polley, in British Columbia (Canada), which took place in August 2014. Following the breaking of a large dam wall that surrounded the discharge pool of a copper and gold pit managed by the Canadian company Imperial Metals, large volumes of heavy metals including nickel, arsenic and lead, were discharged into nearby waterways. Again, the pollutants contaminated flora and fauna, impacting local people, in this case Native Americans belonging to the Salish and Shuswap ethnic groups. Representing the local community affected by the disaster, the biologist Ernest Kroeker attended a meeting called “United in God we hear a plea.” “The nearby lake, contaminated by metals from the mine through a stream after the rupture of the dam, is where hundreds of thousands of salmon every year go to breed. These salmon, climb back from the sea every two years to go and reproduce exactly in the place where they were born. They go through the Quesnel River and come to the Pacific Ocean. When they go down to the ocean, they are fished in the traditional way by local people, who consider the return of salmon a kind of miracle” But those fish are now at risk of contamination, not to be edible any longer and harmful to the health of those who fish them for food. “The mining industry has not felt the need to clean up the lake. Neither have legislators compelled them to do it” concluded Ernest bitterly.

Joana

Joana is a living example of struggle. And hope. In 2007, the Golden Star, a Canadian mining company operating in Ghana, began mining in the district of Pristea Huni-Valley, subtracting portions of land from peasants with brutal methods and without permission. “From one day to the other,” says Joana, “signs saying ‘do not cross’ appeared. But it was May, I could not, not enter the fields, I had to work the land.” The police intervened, arresting her and her helper. So the ordeal began: the detention and then the trial. “I said to the Police that I didn’t break any laws: the land stolen by Golden Star belonged to me and to my ancestors.” Her fight went to court, where “I had to defend myself,” says Joana, “because I could not afford a lawyer.” Nevertheless, a judge told her that she was right, and authorized her to return to her homeland. So a farmer from Ghana became an example for her people, thanks to the determination and the strength that she also showed at the meeting: “United in God we hear a plea.” The Waca, a Ghanaian association that mobilizes communities affected by mining, joined Joana’s fight against the mine. “The open pit mine has brought air and water pollution, which is essential in large quantities for the plantations we live from in our countryside.” Eight years later, Joana can say that the situation has improved, because “people have become aware of their rights against the mining industry.” The brutality of the expropriation of the land was stopped. Under pressure because of the battles fought by the peasants, the Ghanaian parliament passed laws requiring the consultation of local communities before extraction activities start.

1 For further information about the impact of the French oil companies Perenco and Maurel & Prom in the Peruvian Amazonia, see the CCFD-Terre Solidaire et Secours Catholique-Caritas France report published in September 2015 in partnership with CooperAccion et Centro Amazónico de Antropologia y Applicación Práctica :” Le Baril ou la vie ?”. Executive summary available in French and Spanish.

Contact: Denise Auclair

Senior Policy Advisor (EU Policy, Private Sector, Sustainable Development)

auclair(at)cidse.org

EN_The_people_the_church_and_the_mining_robbery.pdf

ES_Los_pueblos_las_iglesias_y_el_saque_de_la_mineria.pdf

IT_I_popoli_le_chiese_e_il_saccheggio_minerario.pdf

PT_Os_povos_as_igrejas_e_o_saque_da_mineracao.pdf

FR__Peuple_Eglise_et_mines.pdf